Obsession: Enigma

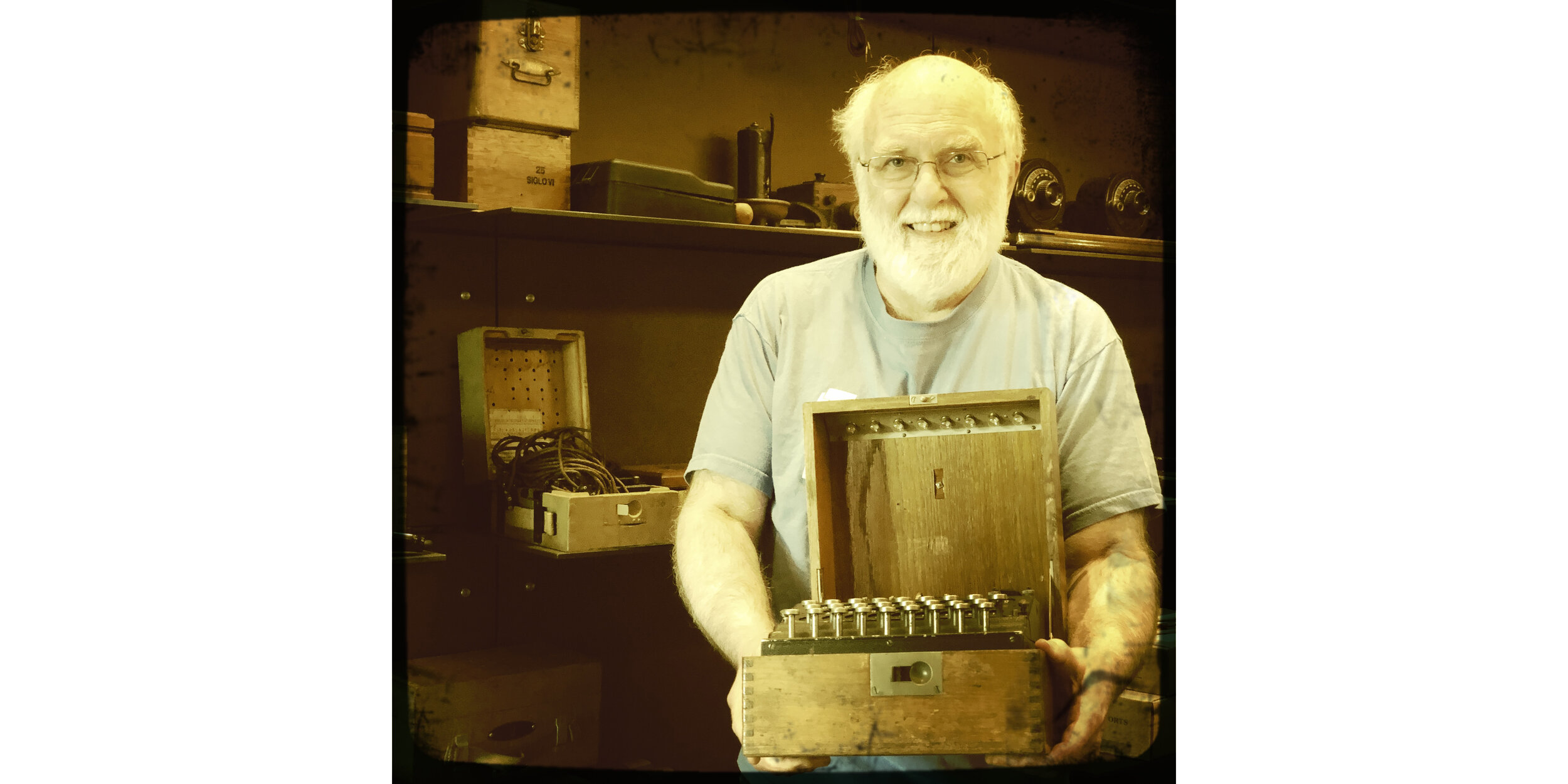

Glen Miranker holds the rotors of the model Swiss K Enigma machine.

OBSESSION #1, REVIEW #3

“I was vibrating. Absolutely vibrating. I couldn't believe how fortunate I was, how lucky I was.”

It’s been well documented that the human phenomenon of obsession, “an idea or thought that continually preoccupies a person’s mind,” can lead to irrational decision-making, extreme actions and perilous situations. Obsession can drive people to pour incalculable time, energy and resources into a pursuit that at best may seem excessive, at worst dangerous or destructive.

How is it that supposedly rational humans can be driven to such irrational extremes? What are the characteristics of obsession, and what are the conditions that provoke it? Do we choose what we obsess over, or does it choose us?

And is obsession always such a bad thing?

To explore this curious human trait, I’m meeting with several extraordinary people, each with their own unique and compelling obsessions. Today I’m speaking with Glen Miranker, former Chief Technology Officer at Apple and owner of an impressive catalog of credentials, among them a degree from Yale and two from MIT. Glen held positions at NeXT and then Apple, where he helped birth the iconic candy-colored iMac. Most significant for our purposes, Glen is captivated by a twentieth century encryption device used by the Germans in World War II to transmit messages in secret code. Archaic though it may appear, in its day this device was highly advanced technology, producing ciphers so sophisticated as to be considered unbreakable.

Fittingly, this badass piece of twentieth century technology has an equally badass name: Enigma.

Glen’s decades-long fascination with the history of encryption and the Enigma machine has led him to acquire four extremely rare and valuable versions of the machine, as well as a seat on the board of directors at the NSA’s National Cryptologic Museum.

In this interview, we’ll triangulate some of the circumstances behind Glen’s preoccupation with the device, and we’ll discover the beneficial outcomes of his obsession. We’ll learn some of the intriguing history of the Enigma machine and discuss its consequential role in WWII, as well as the impact of the Allies ultimately breaking the unbreakable code.

And not to be outdone, my personal obsession dictates we taste a period Armagnac, a 1942 Laberdolive made during the war.

The interview has been edited for clarity and, purportedly, brevity. Buckle up for a glorious geek-out session.

~

Jay Jadot: Let's start simply. Why Enigma? What captivates you about the Enigma machine?

Glen Miranker: The short version of the story is my interest in cryptography was sparked by a couple of fortunate events when I was in grad school. My interest is particularly on the historical side, it became clear to me that the most interesting eras in the crypto world were World War II and now. The big story of course, in World War II crypto, was the Enigma machine.

JJ: What is the Engima machine, it in a nutshell?

GM: The Enigma machine was the workhorse encryption device used principally by the German military in World War II. The Germans, well before the war, realized that substantial communication would be required by Blitzkrieg, and practically speaking that would have to be done by radio.

Therefore, their military messages would need to be encrypted, ciphered and coded because anybody could listen. Part of the planning for that was putting in an elaborate, industrialized cryptosystem of which the Enigma machine was the central part. Military units down to the very small unit size would have one of these machines so that they communicate across and up the military hierarchy.

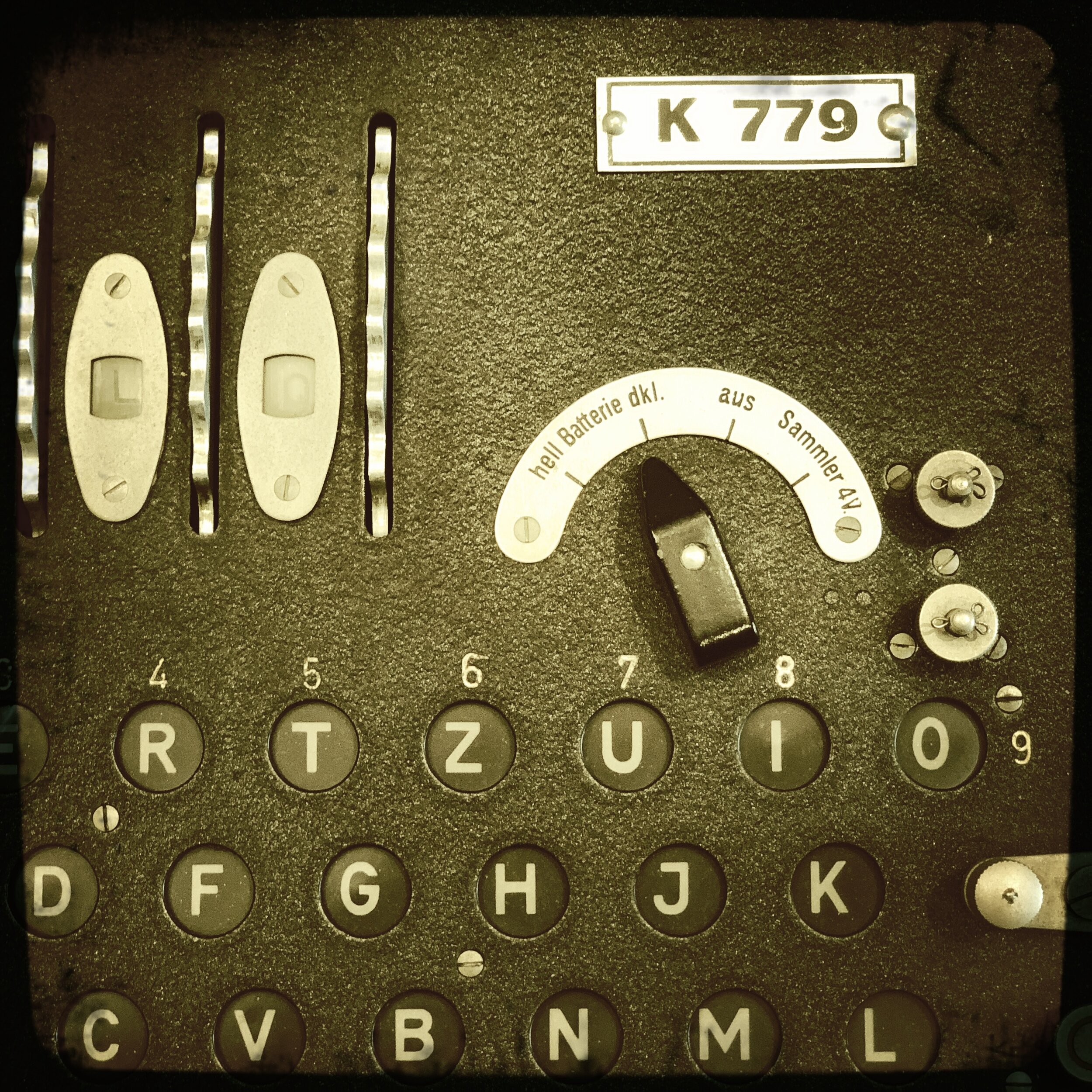

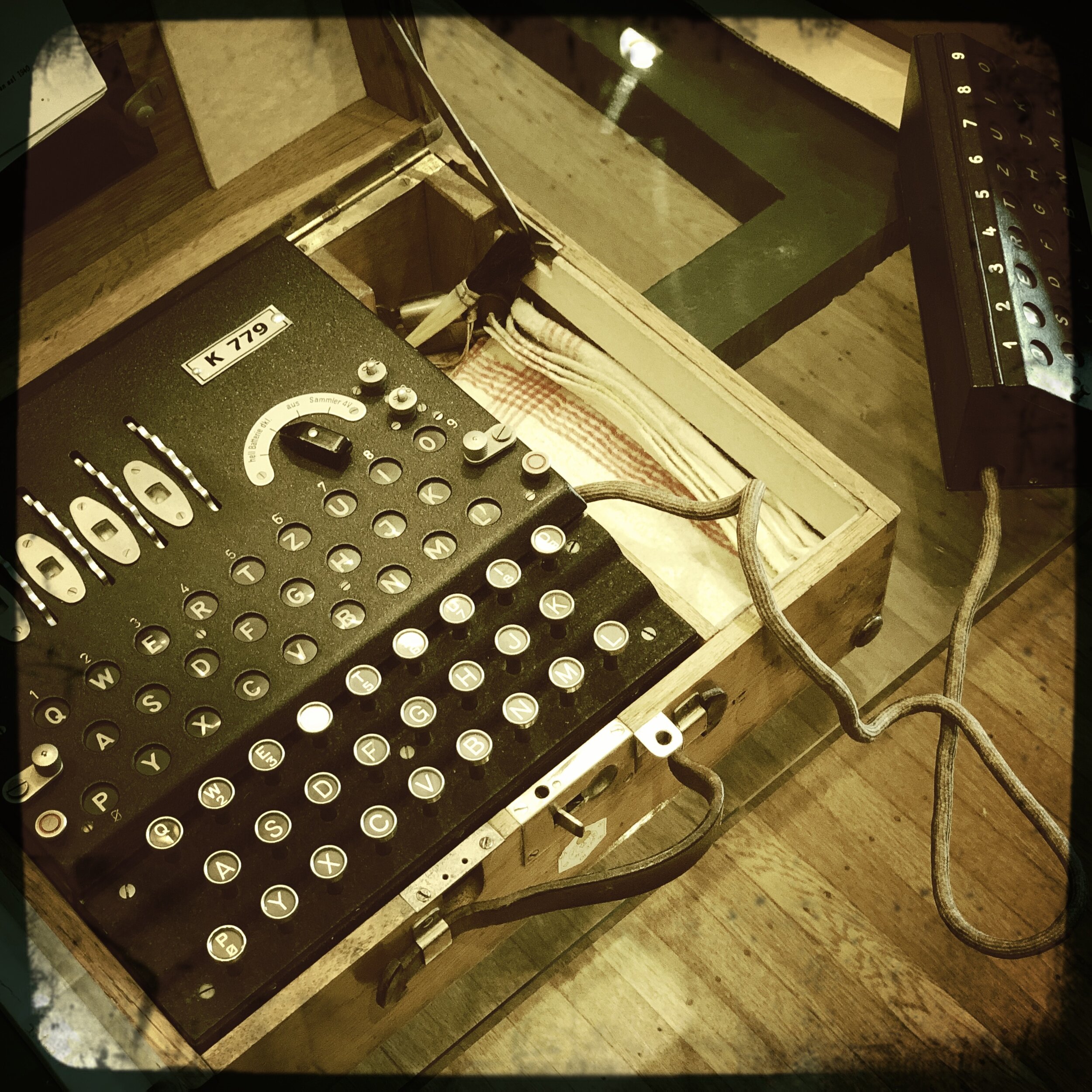

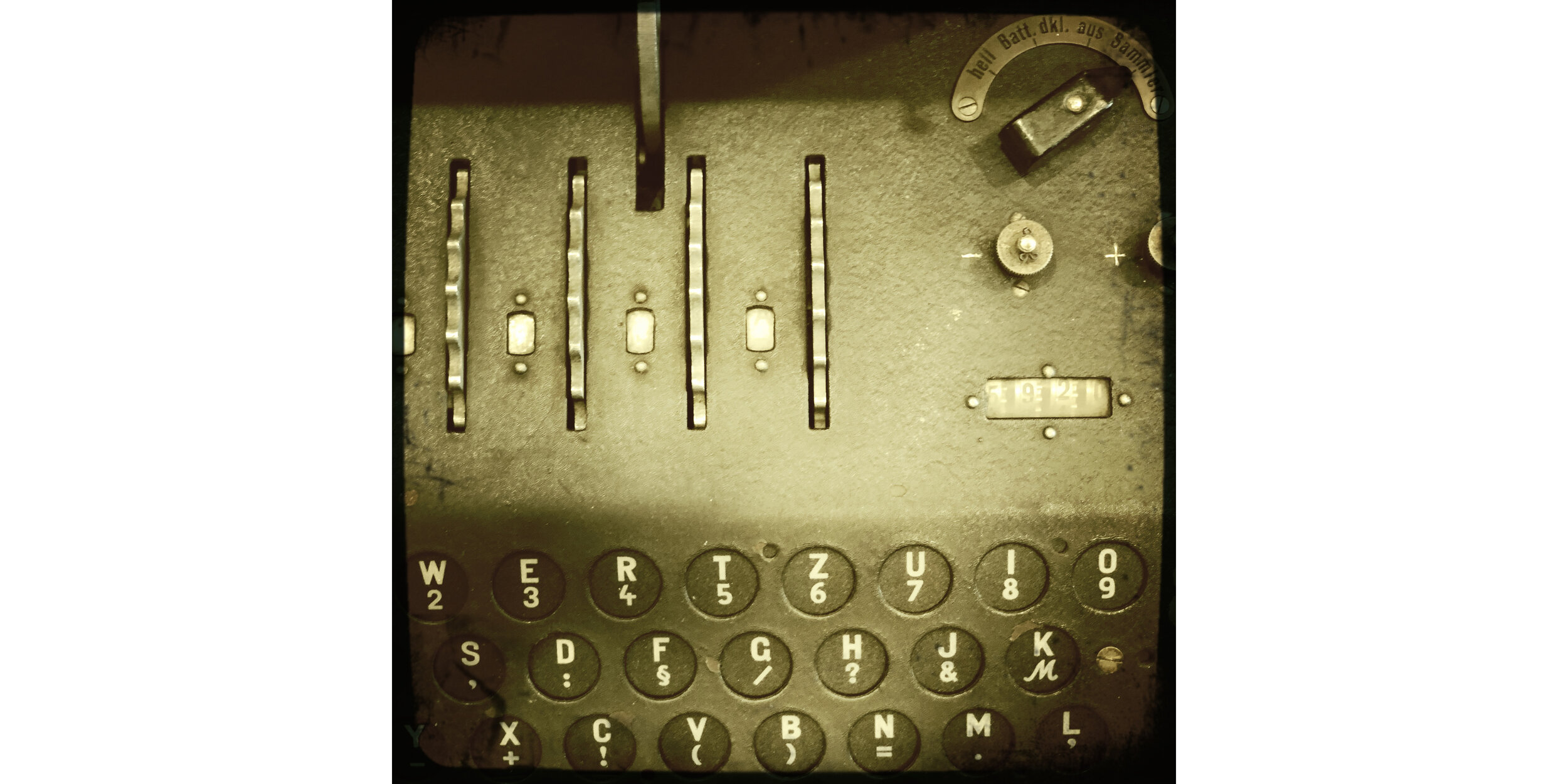

The machine itself is about the size of a large, large portable typewriter, if anybody remembers what those are. They weigh about 40 pounds and there's a typewriter keyboard on them. There's a mechanism which looks vaguely like a car odometer, which is the encryption mechanism. You type your message in. Above the keyboard is a set of lights, which are in the same pattern as the keyboard, and every key you press, a light will go on which is the encrypted version of the character you just pressed. You have a partner on the right, he transcribes the message.

By pressing in your clear text message character and transcribing the enciphered message the character you get the enciphered version, which is then handed off to a morse operator. You do that process in reverse at the other end.

The Enigma G machine with keyboard and corresponding lights. The cover plate is lifted, exposing the rotors and light bulbs.

JJ: The Enigma machine was by far the most advanced ciphering device in its day and was considered unbreakable. During WWII, Allied forces (first the Poles and then more comprehensively the Brits) were able to crack the Enigma code. How significant was this? What effect did that have on the war?

GM: It is fairly easily arguable that the effect was huge. That particularly the British were able to do that is nothing short of miraculous. There are responsible historians, not me, but there are responsible historians who credit the reading of the Enigma code with shortening the war by two years. What this allowed the Allies to do was understand [German] troops' positions, [and in response] move the material in some detail on a reasonably continuous basis throughout the war.

In any number of cases, this was of great importance. For example, decrypting German traffic, and verifying that the deception program for D-Day was being effective, was a critical part of the decision to actually go forward with D-Day. We now know, because of declassified documents, the [truth] around Patton being able to “read Rommel's mind.” Not to detract from Patton's brilliance as a commander, but no, he wasn't reading Rommel's mind, he knew how much gasoline [Rommel] had and where the disposition was, and how many tanks he had in which city in Northern Africa.

JJ: That was because of deciphering Enigma?

GM: That was because of deciphering Enigma.

JJ: Tell me when you first discovered the Enigma machine.

GM: The event that started all this was just a chance event. I had no particular connection, casual or otherwise with cryptology in grad school, but one of the professors on my thesis committee was Dr. Ron Rivest. He and Alan Edelman and Adi Shamir were the gentlemen who figured out the first practical implementation of what's known as public-key cryptosystems.

Now, without going into detail, let me just say that every time you see the S on HTTPS with your secure connection, that is done using public-key crypto. It was a sea change in cryptography. That sparked a general interest on campus. Suddenly, everybody wanted to get into cryptography [because of] their breakthrough,

Ron had invited a guy named David Kahn to come lecture. David Kahn has written a number of books, but at the time, he was best known for having written a book called The Codebreakers, which is still the best general book on the history of codes and ciphers. He was on campus and he gave the 40-minute version of his book as a talk. He's a wonderful speaker, was absolutely stirring. That talk plus then the reading of his book is what sucked me in.

JJ: When was that?

GM: Let's see, that would've been 1978.

JJ: What led you to start collecting the Enigma machine?

GM: I was so taken with the enigma machine because of its importance. Also, there's a lot of romance about it. How many movies has the Enigma machine figured in either casually or explicitly in the last couple of decades? There's a real fascination with the machine in the story, even when it's not the main feature of the story. When I was a kid, I started reading about crypto in general, World War II cryptos. I said, "Jeez, if it ever became possible and I had enough money, I would like to own an Enigma machine."

All these things came together in '94, '95, something like that. I have a more serious collection [of] Sherlock Holmes books and manuscripts. I bring that up because I became aware through book collecting, that there's a difference between a serious collection and an accumulation or a trophy. A collection is the assembling of items, which together tell a story. I became interested in having items around the German rotor machines of World War II [as a way] of telling a story. If you can manage it, it is a wise thing to do to try and narrow the story you're trying to tell as much as it's practical.

“A collection is the assembling of items, which together tell a story.”

JJ: That's why I don't drink Cognac.

GM: There are plenty of rabbit holes to go down on that. It could be Cognac, it could be Single Malt Scotch, it could be a fancy Bordeaux. There's no shortage of them, but because of my interest in Enigma, I decided that would be my focus.

JJ: I love that definition of your obsession. It's not so much about the possession of the object or the trophy, it's about the means to tell a story.

GM: For me, it means to tell the story. Again, if I can use this as an exemplar or an analogy, my book collecting, if I get a first edition of The Hound of the Baskervilles, it's got the same words as the copy you can download for free. What's interesting about that book has nothing to do with the words that are in it.

JJ: Then what is interesting for you about that book?

GM: The publication history, or it could be the particular book, for example, maybe an association copy, maybe a copy that was signed by Conan Doyle. What was the occasion on which he signed it, and why did he sign it? What's the story behind getting the book published? For example, talk about The Hound, it was published in the United States by this fellow S.S. McClure. It's already too late to make a long story short. I'll just say that McClure was nervous about the success of the book. Suffice it to say, he was hopelessly wrong. There were 50,000 copies sold in the first three months, but he was nervous. It went through about seven different issues in the first three months. Tracking these issues, how many were done? How the book was altered from issue to issue, in response to his perceived marketing requirements of the book I find fascinating.

Now, similarly, with the Enigma machine, there's not one machine. The very, very first Enigma machine with that name, with that cryptographic algorithm, was [made in] 1918. There's an extremely small number, almost none of which are extant over the years leading up to World War II. But even in World War II, even among the Germans, there was a particular flavor of the machine used by the army, different flavor of the machine used by the Navy. You had a different flavor used by the Abwehr, which was the German equivalent of the CIA. You had a different version used by the German railroads.

JJ: You used the word ‘flavor’ because as an Armagnac drinker I can relate.

GM: Yes! Absolutely! It's exactly what I was thinking! You've seen [the Enigma machines], they are genuinely different [from each other]. They're not interoperable. The army and the air force are interoperable, but except for that, they're not interoperable. It's not just the color of the metal or the shape of the enclosing box. They are different.

Glen Miranker’s four Enigma machines. From front to back: Enigma I, Enigma G, Swiss K, Enigma M4.

JJ: If the Enigma was never used in World War II by the Germans or by any power, it would probably not have the story, and therefore would probably not be worthy of collection, nor telling the story.

GM: I think that's fair.

JJ: It's probably the combination of both the brilliance behind the machine itself, the aspect of cryptography that is particularly interesting to you, and of course the history, the combination of those things is what makes it so powerful.

GM: If you look at the history, at the events associated with Enigma, they're nothing short of fantastic. If we look at the World War I to World War II interwar period, the United States had essentially no professional crypto analytic organization, and the crypto devices that the US used were almost laughable they were so archaic. The British were quite a bit more advanced, but they weren't worried about the Germans. The peace treaty had taken care of Germany as a military effect. The British were consumed with their rival naval powers, Japan and the US.

By the way, as an example of that, [the British] did have a competent crypto group, but the German branch of the crypto group in Great Britain during the interwar years was a number like 6, 8, 10 professionals. The hardcore crypto analysts [numbered] half a dozen, maybe smaller in the German branch. However, the Poles were paying attention. The Poles were very nervous. They're looking over their shoulder to the west and there's Germany, which has designs and all that. They're looking over their shoulder to the east and there's Russia. Holy mother of Pearl! [The Poles] had a super-competent crypto analytic service. They were watching the Germans and their machine codes, Enigma, and there were a couple others, very carefully. The Poles made the deep fundamental breakthroughs during the interwar years.

JJ: You mentioned in the 90s, you were in a position to be able to acquire a machine if you could actually find one. Tell me about how you found an Enigma machine.

GM: I learned in mid-80s that the NSA had been running, and still runs, an annual conference, every other year in the Fort Meade area on the history of cryptography. It's open [to the public], all you need is an admission ticket. I took myself to go to this conference. I've been going every two years since. Mainly it's a three-day event and there are parallel sessions. The topics are absolutely fascinating.

Of course, they vary from year to year, but almost every year you can be sure there'll be some Enigma-related topic. I was chatting with some of the guys over drinks after the hard work of the day, and I mentioned to this fellow Tom Perera my captivation with the Enigma machine and that I would dearly like to own one. Tom Perera is Mr. Enigma machine. He has found and/or restored some ungodly number of these machines. Lovely fellow, he's long retired.

I said I wanted to a naval Enigma, and I think everybody wants a naval Enigma, and he located one. I visited him in his home in the wilds of Vermont and came home with an Enigma machine.

Glen’s four-rotor naval Enigma M4, used on German U-Boats and Kreigsmarine Battleships. It constitutes an upgrade from the earlier naval model with eight different interchangeable encryption rotors, three of which were in use at any one time. The fourth rotor (left), while not interchangeable, adds an additional layer of encryption

JJ: When you acquired the machine, what was that feeling like? Was it deeply satisfying to you?

GM: I was vibrating. Absolutely vibrating. I couldn't believe how fortunate I was, how lucky I was, how nice an example it was. To go to the other extreme, there's a fairly steady supply of what are called relic recoveries. Take a look on eBay, if you're interested, almost in any week, they're two or three, and these are machines or fragments of machines that are found in the bottom of a lake, buried in the woods. You can imagine the condition they're in.

That's the other extreme. You've seen my machines they're in great shape.

JJ: You were vibrating, and why? Was it because you were now holding and connected to that piece of history?

GM: That's exactly right. That this is an astoundingly important, and innovative device and history, a collection of math and science and cracking it were all staggeringly important, impressive to me. Now I could touch it.

JJ: It takes history and science out of the realm of the conceptual, and makes it that much more real and concrete and in your hands.

GM: Certainly, for me, there's a world of difference between a picture and actually being able to touch and smell something. People in general experience this on all kinds of levels. We go to zoos to actually look at the animals. It's far more satisfying, illuminating, than either watching it on a screen or looking at a book. The experience is just different. It's extremely different when you have the haptic, you can actually touch it and see. What do the keys feel like? How hard would they press? How complicated with your own hands is the setting up of the key in the machine? It's completely a different experience than reading about it or even watching it on YouTube.

It's not for everybody. There are people who aren’t moved or appreciate having these kinds of experiences, but there are those that do. A fellow who has captured that idea brilliantly is a guy named Nicholas Basbanes, he wrote a book called A Gentle Madness. It's all about book collectors and book collecting, and he absolutely captures that not everybody collects books. In fact, very few people collect books. In fact, a shrinking number of people collect books. For those who do it is a very strong, very powerful experience, which involves multiple senses, and a different sensibility about the objects. I have a different relationship with a book than somebody who doesn't read at all, to take an extreme example.

“There’s a world of difference between a picture and actually being able to touch and smell something.”

JJ: I will have to research this book and read it because that is exactly what interests me and fascinates me about our various obsessions. But I will download it because I'm not a book guy.

GM: I honestly don't know if it's on Kindle. That would be quite ironic.

JJ: You own four Enigma machines and I understand you have had some clandestine-type experiences acquiring them?

GM: There was one that I would think is amusing and one which borders on clandestine. I'll give you the amusing one first.

The beginning of this is a call from a friend of a friend of a friend [who directed me to] a fellow who owned a junk shop. Literally, a junk shop. Not an antique shop, a junk shop, in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. He had this Enigma machine. He would not tell me where it came from. I was able to talk him out of consigning it [to auction] and just selling it to me. You know, “the vicissitude of auctions” and the 15% cut you would have to give, and the 20% cut that the seller would have to pay, so a third of that is overhead, it doesn't figure in his proceeds. I got it at an attractive price. I wish the story also included, "I got it for $2,000." But no, it was a very good price, but it was a real price. It came from Bensonhurst, Brooklyn.

JJ: And the borderline clandestine?

GM: I got a call from a fellow in the larger Enigma community who said he knows of this fellow in Buenos Aires who apparently has an Enigma G. That's the kind of enigma machine that was used by the Abwehr. The Abwehr was the German’s equivalent of the CIA, intelligence and espionage. It’s very different, it's mechanically unique in a number of ways.

I got his phone number, and we agreed on a price in reasonably short order. The difficulty was arranging the exchange. He insisted that I fly to Buenos Aires in person with a shopping bag full of cash and we do the swap in person. I wouldn't walk down a [city] block, let alone cross international borders, with that much cash in my possession. We had a series of conversations that literally spanned two-plus months on how we would manage this.

I was eventually able to talk him into what I think was rational and sensible a process. I suggested find any local correspondent bank. I said, "Anywhere in the United States." [The seller made arrangements with] a bank in El Paso, Texas. I flew down to El Paso, Texas, go to the bank and the manager lets me examine the machine. I said, "Great." Then, I arranged a wire transfer to the El Paso bank, and the bank manager verifies the money is there, let me leave with the machine.

JJ: How did he get the Enigma machine from Buenos Aires to El Paso?

GM: That I don't know. He could've put it in a FedEx.

JJ: What was it like bringing that Enigma machine home? Did you feel like you had just gone on a hero’s journey?

GM: This was huge. An Enigma G is huge. At the time I acquired the machine, the best records I could find listed some number like six, seven, or eight of the G machines [known to exist]. The Abwehr is a very small agency relatively, certainly compared to the army or the air force, which [used] thousands of machines. Over the course of the war, they were close to 10,000 army air force machines made.

The best available evidence is the number of machines made for the Abwehr was a number like 100, 80, 140. There's not great ironclad records but it's a tiny number. There was also some real drama around G machines in general, not my machine. Have you heard of Bletchley Park?

JJ: Yes.

GM: They had a G machine on display and it got stolen. It's in the paper, in The Guardian, you can find the articles about it and it was held for ransom.

JJ: Wow. That's ballsy.

GM: Yes. It was eventually recovered without paying the ransom. It's still unclear exactly what happened.

JJ: So you got home with the Enigma, did you sleep with it on your nightstand…

GM: No, smelled! All the oil and stuff. Smelled! I had more than a couple of sessions where I just looked at it. You've seen the machine, it's really remarkable, the gearing mechanism, and so on and so forth. [Only] a handful of the messages [from this Enigma model] were cracked. Again, a real tour de force. By and large, it was unbroken.

JJ: Perhaps the G was the most successful of the Enigma machines in that their numbers were small and the ciphers were almost never broken.

GM: My vague recollection is that the size of the [British] unit focused on other [types of] codes was a few tens of people. The number of people on the Enigma code, counting everybody, was 8,000 or 9,000. The number of people being paid by the end of the war was just shy of 10,000.

Then when you think about it, the number of Enigma messages that were cracked, never mind the number that were attempted, but the number of Enigma messages that were cracked at the peak of doing this, which was, I don't know, late '44, or something like that, was 3,000 or 4,000 a month. There's a lot, a lot, a lot of recovered traffic. Each message had its own key. Every single message. It's not like you got the key for the day or the key for the month. Every message that came in needed the personal attention of cryptanalysts.

JJ: It was amazing that the allies were able to keep their efforts a secret.

GM: Absolutely astounding. I'll tell you a cute story about that. I was at Bletchley Park, there's an annual event called the Enigma Reunion. Besides [presentations of] papers and demonstrations and stuff like that, a substantial though shrinking number of the folks that were actually working at Bletchley Park [attended]. In maybe my first visit, I was chatting with one of the [crypto operators]. I asked her some question like, "What was a workday like for you?” She said, "I'm sorry, I still can't talk about it." I said, "You know you've been freed from the Official Secrets Act 1989," she says, "I know, but I just can't talk about it." One of the things you don't get in these history books is, "Well, what did you do? How was your breakfast? How did you get to work? How did you get your work assignments? Who did you work with?" and I was interested in those things. Anyway, she wouldn't.

Another story, if I may…

JJ: Please.

GM: I spent some time with a couple, the guy is now gone, Oliver and Sheila Wong are their married name. He was what's called the menu writer, what today we'd call a programmer. He would write out the programs to run the Turing bombes to do the cracking work. Somebody had to look at the messages and all the information associated. There was all kinds of information that they would use to get clues like "who was the operator who had sent the message?” [the German operator might have] certain bad habits [that can be exploited to crack the cipher]. Oliver was the guy who took this cloud of information and would write a set of instructions for how to run the bombe. He was a menu writer. Sheila was very competent in both Italian and German. She was actually using her language skills. She worked on cracking Harbor Codes. There were these very quick, simple codes that were used by shipping when you're close to port either coming in or going out. There was no reason for them to be hyper-hard to crack because they were only of value for a couple of hours.

Anyway, they met at Bletchley Park. To keep these people from going mad, they had any number of diversions. They had tennis matches, they had rounders (it's what you call baseball) and all that stuff. Well, they had Scottish reel dancing, and so on, and both Oliver and Sheila were big-time Scottish reel dancers and that's how they met. They got married a year or two after the war. They did not know what [the other] did. They did not share that with each other, even after they were married, they told me, until they were released from the Official Secrets Act [in 1989].

I don't know how often these dances were, but they're dancing together, and they're falling in love and [have] no idea what either of them did. I'm just saying the compartmentalization, even among the professionals.

JJ: There's also that element in collecting, the hunt. We're hunter-gatherers by nature, and we love the hunt.

GM: Well, I particularly like the hunt, not only because the hunt itself is exciting, but that's where you learn an awful lot of what you end up learning, is during the hunt.

JJ: It's an educational process.

GM: Yes, exactly. I typically learn a great deal after I've gotten an object, to start digging into the object. For example, the Kriegsmarine machine, I was able to uncover, through the work of others, the history of where this machine had been after I had acquired the machine. Knowing it was delivered to France, knowing it made it up to Trondheim, and being pretty certain that must have been used by the Norwegian Coast Guard.

JJ: So you acquire, arguably, this holy grail of Enigma machines, why keep collecting? Why not just stop there?

GM: (sarcastically) What are you talking about? (laughter) What did you say? What?

JJ: Obsession knows no boundaries.

GM: Fair enough. The question in the case of the Enigma machines is, what else might there be that I would be interested in? There are other machines, and in fact, I'm hot on the trail of one even as we speak.

JJ: Now, I don't want you give anything away that might--

GM: I wouldn't.

JJ: What can you tell me about the hunt you're on now?

GM: The Germans, some of the relevant high command centers had some suspicions that the Enigma machine was not sufficiently secure, and it was pretty difficult to use. So they started a development program within the relevant part of the military organization to build a replacement for the Enigma machine.

They in fact did. They had the first working machines in mid-'44, maybe a little later, very romantically called the SC40. However, it was still pretty big and heavy, but it was about this big and was not electrical, that was one of the advantages. The Enigma machines need a battery. Especially in those days, batteries didn't last very long at all.

JJ: If you were out in the field, and you ran out of batteries, you were S.O.L.

GM: That's it. This machine was run by a crank. It had this crank on the side instead. It's just an advanced mechanism. It looked like a cheese grater when it was called the “Hitler grater.”

JJ: Do you think there's a point at which you've learned everything there is to learn, you've collected an adequate number of Enigma machines and the obsession will fade?

GM: It's possible, but I don't think I'll live that long.

JJ: There's so much still to discover, which I think is one of the keys to obsessions, to learn.

GM: I'm particularly confident about that because I go to these conferences. There are folks that are turning up the stuff, there are interesting papers. I get papers with some frequency at these conferences. I have something to tell these experts, which they didn't know, or at least interested in hearing about again, or whatever. There is truly no end in sight.

JJ: There's always something new to discover.

GM: Interesting things. For example, it’ been a couple of years now, I [presented] a paper in a number of places, and raised a lot of eyebrows, where I argued that the Enigma machine was not that important in the Battle of the Atlantic. Overall, yes, not in the Battle of the Atlantic. I went through some careful arguments that showed that the Allies were only moderately successful, and relatively late in the war, [at] breaking the naval code.

JJ: You're clearly a history buff, you're clearly an analytic type who enjoys engineering codes and ciphers. This obsession is a perfect marriage of multiple interests of yours.

GM: I agree.

JJ: Am I missing any piece?

GM: It's the technical underpinnings. And by the way, I am no good at cryptography. I am absolutely convinced that really gifted, really good cryptographers' brains are wired differently than mine.

JJ: I can crack the stuff in the Sunday paper, but that's about the limit. You've been tremendously generous with your time. Let me offer a taste of this Armagnac.

GM: Thank you. I think I told you that I love Armagnac. Not quite my thing, but Scotch is.

JJ: This a 1942 Laberdolive Domaine de Jaurrey. Tell me what you think of it, and what you smell, and what you taste.

GM: Licorice. Maybe some cassis?

JJ: I think so. What struck me at first was a saline quality. There's a little bit of a salinity.

GM: Yes, yes, yes. There's definitely more fruit in it. I'm trying to tell which kind.

JJ: A little stone fruit.

GM: That's exactly what I was thinking. Peach?

JJ: Yes, peach, nectarine.

GM: No, not cassis. Peach or nectarine. That's extraordinary.

JJ: This has got a certain mellowness and elegance to it that is quite attractive. When this was made, 1942, it was Vichy France in this region, and the enigma machines were in use in France pretty widely at that time. We can see and touch history, we can hold it in our hands, and we can taste history too. That's pretty cool.

GM: I haven't had that many, but this is easily the most amazing Armagnac I've ever had.

JJ: Have I created a new obsession?

GM: (laughing) Oh, I hope not.

~

In my quest to “decode” the phenomenon of human obsession, this conversation with Glen affords the opportunity to perhaps derive a pair of key characteristics.

First, the focus of obsession may well lie at the intersection of our interests. For Glen, the Engima machines he has spent countless time, energy and treasure pursing lies the intersection of cryptography, history and technology. These are all compelling in their own right but are amplified when it occupies the center of the three overlapping circles of interest.

Secondly, for all its seeming irrationality, obsession offers us the opportunity to learn. The curiosity drives us, and what is learned we may find profoundly enriching.

Deep appreciation to Glen Miranker for his willingness to share his passions with us. Lift your tulip-shaped glass and toast to the former Apple CTO…here’s to the crazy ones.

1942 Laberdolive Domaine de Jaurrey

43% Alcohol by Volume

Color: Amber with orange and gold highlights.

Nose: Caraway and green raisin, backed by sweetness and subtle salinity.

Palate: Baked apple and soft apricot followed by a blitzkrieg of rum raisin and woody rancio.

Finish: Licorice, cocoa powder.

Summary: Made in Vichy France shortly after the German invasion, this Laberdolive is as solid an offering as you’d expect from a premier producer. Three cheers for growing, harvesting and distilling while under the thumb of a foreign power. A little act of defiance is now a little taste of history.

When to drink: When taking the time to consider the past and appreciate the present.

Score: 88

DECODEAbwehr Enigma G-111UKW 6F 4DII 3C 7GI 19S 10JV 5E 21Uwubky xevje ltcmf jxgbu knekt mdcst jdlwg qhfpt yjltv pwgwq sykzu srhzp deexk csefo bqpnd cfuvb ninae ysjts uimvi smsly zlhjj bwxdj swsyq nmq

AOML Rating scale:

<75 Not recommended

75-79 Average, contains some flaws

80-84 Good, well-made Armagnac

85-89 Very good, an Armagnac with special qualities

90-94 Outstanding, an Armagnac of exceptional character and style

95-100 Classic, an Armagnac for the ages